More than 150 UK-oriented YouTube channels pumping out fabricated or inflammatory videos aimed at Labour reached almost 1.2 billion views in 2025, according to unpublished research by the digital rights group Reset Tech seen by the Guardian. The channels, which collectively posted about 56,000 videos this year and amassed roughly 5.3 million subscribers, were described by researchers as part of a high-volume “synthetic news” ecosystem that relied on sensational claims, misleading presentation and, in many cases, AI-generated scripts and voiceovers tailored to British audiences.

The findings, published by the Guardian on Saturday, add to widening concerns in Westminster and among regulators that cheaply produced, algorithmically promoted political content is outpacing the ability of platforms and governments to respond, particularly as generative AI lowers the cost of producing persuasive audio and video at scale. They also underline how quickly political misinformation can spread even when it is not clearly tied to a state-backed influence operation, and may instead be driven by ad revenue and engagement.

YouTube said it removed all 150 channels flagged in the research after being approached by the Guardian, citing breaches of rules on spam and deceptive practices. The company said it enforces its policies regardless of political viewpoint and that content designed to mislead users or exploit the platform’s systems is prohibited.

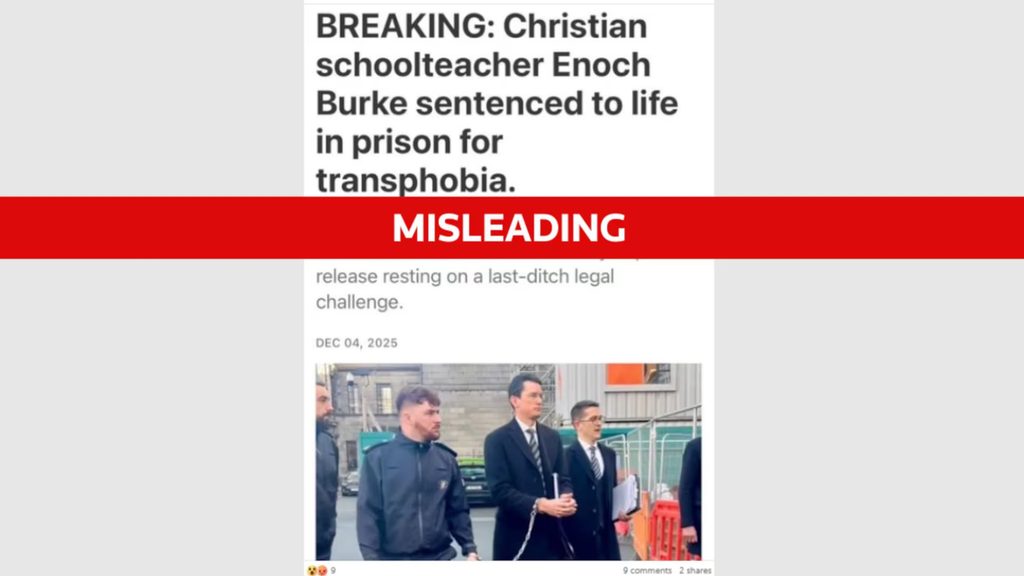

Reset Tech’s dataset focuses on English-language channels oriented towards UK politics, many styled to resemble legitimate news outlets through logos, “breaking news” graphics and thumbnails that mimic television bulletins. The videos typically used a familiar format: a still image of a politician or a short loop of parliamentary footage, paired with an urgent-sounding voiceover in a British accent and a headline-like title promising dramatic developments.

Among the most common targets were the prime minister, Keir Starmer, and the chancellor, Rachel Reeves. Reset Tech recorded 15,600 instances in 2025 where “Keir Starmer” appeared in titles or descriptions across the channels it analysed. The narratives were often personalised and absolutist, with repeated claims that senior Labour figures were on the verge of arrest, had been “sacked” or publicly humiliated, or were facing a sudden collapse of authority.

Examples cited in the Guardian’s reporting included channels with names such as “Britain News-night”, which posted videos alleging Starmer and Reeves faced arrest, and “UK NewsCore”, which promoted claims that Nigel Farage was “ousting” Starmer and that the prime minister had been “sacked live” and thrown out of parliament. Other channels pushed fabricated stories about a confrontation between the royal family and the Labour government, designed to provoke outrage and amplify existing culture-war tensions.

The content was not presented as parody. Its power, researchers argue, lies in how closely it imitates the cadence and packaging of conventional political coverage, while substituting verifiable reporting with rumour, insinuation and invented “explosive” developments. Viewers can arrive at such videos through YouTube’s search function, external links and, crucially, the platform’s recommendations, which are shaped by watch time and engagement.

Reset Tech assessed the UK-focused cluster as predominantly opportunistic and profit-driven rather than an obvious arm of a foreign intelligence campaign. The group’s UK director, Dylan Sparks, told the Guardian that the channels appeared to be exploiting “clear weaknesses” in YouTube’s moderation and monetisation systems, generating attention and advertising value from content that distorted political debate. In that analysis, the concern is less that each channel has a strategic political sponsor and more that the infrastructure is available to anyone who wants to manipulate public discussion, including hostile states.

The research situates the UK channels within a broader European map of 420 “problematic” channels across multiple languages, including German, French, Spanish and Polish. In that wider set, Reset Tech said some channels appeared to be run by Russian-speaking creators, though it did not characterise the UK cluster as demonstrably state-directed. The organisation’s work echoes a growing body of research across Europe and the US showing that “synthetic” political media can be produced and iterated rapidly, shifting narratives week by week to match news cycles, polling swings and cultural flashpoints.

The scale of output cited by Reset Tech helps explain how such channels can accumulate large audiences quickly. Uploading in high volume increases the chances of being surfaced by algorithmic systems, and also allows creators to test which themes perform best, then repeat those formulas: immigration and crime, accusations of elite corruption, insinuations of conspiracy and the promise of imminent dramatic retribution against political opponents.

It is also a business model that mirrors what other researchers have labelled “AI slop”: low-cost, repetitive material mass-produced to capture attention and advertising revenue rather than to build a stable editorial brand. The Guardian linked the YouTube ecosystem described by Reset Tech to similar dynamics documented elsewhere on the platform, including rage-bait celebrity “cheapfakes” that use misleading edits and sensational scripts to drive clicks.

How much money the UK political channels generated is not publicly known. YouTube does not routinely disclose channel-level earnings, and even channels that are not formally in the YouTube Partner Programme can earn money via alternative routes such as affiliate links, sponsorships or directing audiences elsewhere. Still, the combination of nearly 1.2 billion views and the production style described by researchers points to an ecosystem designed around monetisation at scale.

The Guardian’s report comes at a politically sensitive moment for Labour, which won a landslide general election victory in July 2024 and has repeatedly framed trust in public life as a central theme of its governing agenda. A Labour spokesperson said the spread of fake news online represented a serious threat to democracy, arguing that both profiteers and hostile foreign states had incentives to flood digital platforms with misleading content, and urging faster action by technology firms.

The issue also lands amid an evolving regulatory landscape. The Online Safety Act, passed in 2023, is being implemented in stages through 2024 and 2025 as Ofcom develops and enforces codes of practice. The regime is designed primarily to reduce illegal content and protect children, backed by the threat of major fines for serious non-compliance. It is less clearly designed to tackle political misinformation that is false but not illegal, leaving a grey area in which sensational and misleading political content can proliferate even when it does not meet a legal threshold for removal.

Ofcom’s own research published in November found that 43% of UK adults said they encountered misinformation or deepfakes, and that among those who saw false information, around 70% reported encountering it online. The figures do not isolate YouTube from other platforms, but they illustrate the breadth of exposure and the challenge regulators face when harms are distributed across formats, from doctored videos to synthetic voiceovers.

Alongside safety regulation, ministers have also been exploring the economics that can reward harmful material. The government’s Online Advertising Taskforce, convened by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, is intended to bring industry and government together to improve transparency and reduce harmful and illegal advertising. The Guardian framed the YouTube findings as a case study in how the ad-funded attention economy can subsidise misleading political content, particularly when production costs fall and output rises.

YouTube has spent the past two years updating policies intended to address manipulated media and the mass production of low-quality content. The platform has rolled out rules requiring creators to disclose realistic synthetic material in some contexts, including election-related content, and has refined monetisation standards to target repetitive, mass-produced videos. It has also pointed to large-scale enforcement actions in other contexts, including takedowns of state-linked influence operations and election-related removals across Europe.

However, Reset Tech’s core criticism, as reflected in the Guardian’s reporting, is that enforcement often appears reactive and uneven. In this case, the 150 channels were removed only after the Guardian presented the findings to the company. That sequence is likely to intensify scrutiny of whether platform detection systems can identify political “synthetic news” quickly enough to prevent it spreading, and whether internal incentives favour leaving borderline content online until it becomes a public relations problem.

The Guardian’s report notes that some of the content had already been removed before its inquiry, suggesting automated systems did catch part of the network. But the volume of material that remained online, researchers argue, indicates that large quantities of misleading political content can persist long enough to build audiences and generate significant view counts.

There are also methodological questions that will shape how the findings are interpreted. Reset Tech’s research has not yet been published in full, and the Guardian’s story relied on figures and examples provided by the organisation. Reset Tech is an advocacy-focused NGO that campaigns for stronger platform accountability and a “reset” of the relationship between technology and democracy. Supporters see such groups as a necessary counterweight to opaque platform power, while critics argue that advocacy organisations can bring their own biases. In practical terms, the unanswered questions include how Reset Tech defined “UK-oriented” channels, how it classified content as fabricated or inflammatory, and how it estimated the total views associated specifically with 2025 uploads.

Even with those caveats, the patterns described will be familiar to researchers and regulators tracking the industrialisation of misinformation. AI-generated scripts and voiceovers can be produced in minutes, allowing channels to respond rapidly to headlines, create the impression of constant “updates” and overwhelm moderation systems through volume. The use of British-accent narration and UK news-style branding illustrates how easily synthetic media can be localised, making it feel culturally proximate even when creators are anonymous.

The wider security context is also shifting. Earlier this month, the foreign secretary, Yvette Cooper, warned that Russia and other states were using AI-generated videos and disinformation as “hybrid threats” to undermine support for Ukraine and deepen domestic divisions, naming the so-called “Doppelgänger” ecosystem as an example of coordinated deception. While Reset Tech did not characterise the UK-focused set of channels as a direct arm of such an operation, the overlap in techniques has fuelled concern that profit-driven networks can provide ready-made distribution channels and tested formats that are attractive to more strategic actors.

For YouTube, the immediate enforcement action will not end the problem if creators can reappear under new names, or if other channels adopt the same tactics. For government, the challenge is balancing freedom of expression with the need to prevent deception at scale, particularly when the content is political but not necessarily illegal. And for audiences, the central issue is trust: as synthetic production becomes more convincing and more common, viewers may find it increasingly difficult to distinguish reporting, opinion, satire and fabrication, especially when the packaging imitates the authority of established news.

The Guardian’s report ends with a blunt measure of that reach: 1.2 billion views in a single year, generated by channels that, until this week, were largely unknown outside the ecosystems they served. YouTube says those channels are now offline. The question for 2026 is whether the same model can simply be rebuilt faster than the systems designed to stop it.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!