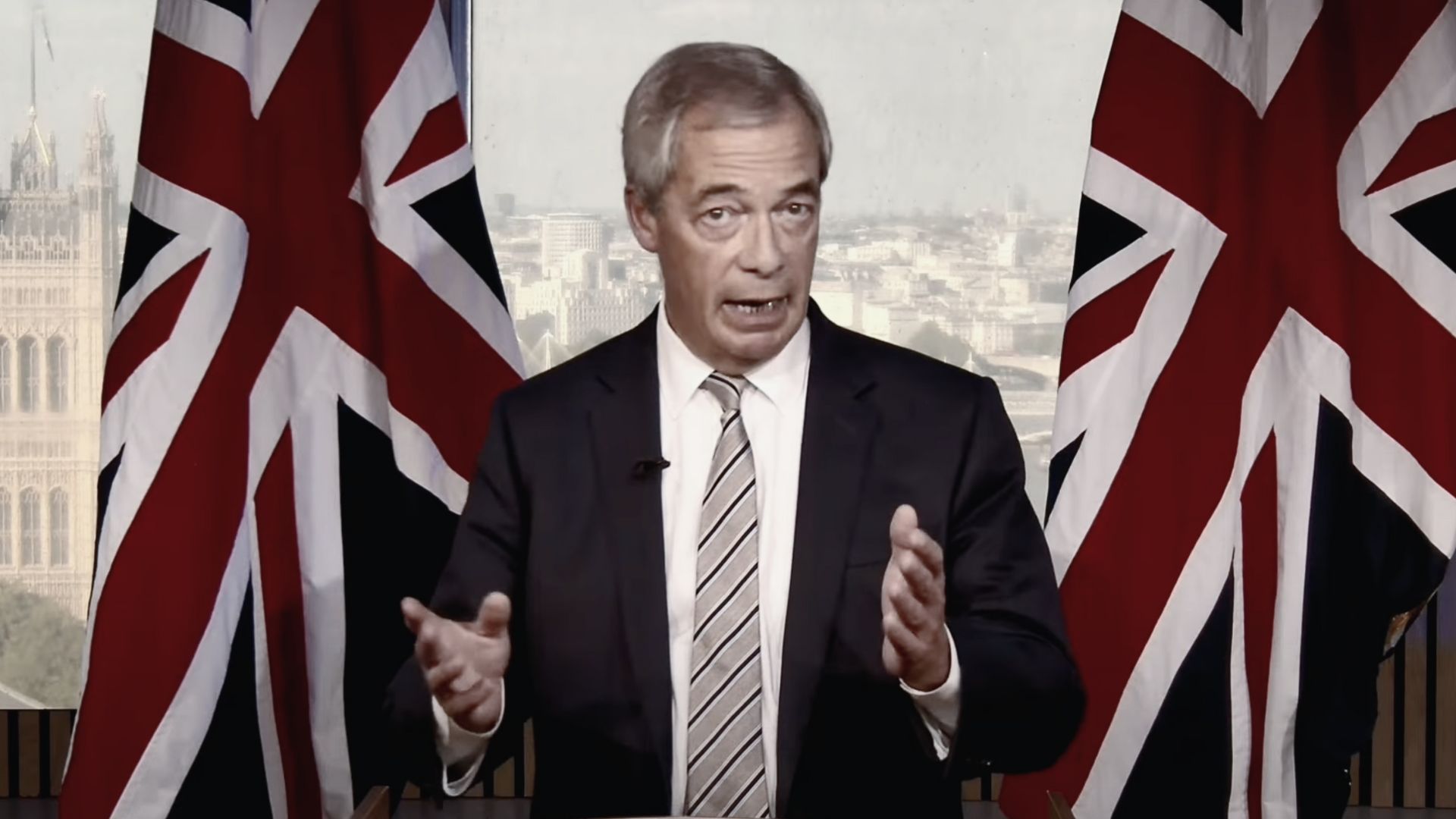

Nigel Farage is, on current polling, closer to Downing Street than at any point in his turbulent political career. A new constituency‑by‑constituency model from YouGov—based on 13,000 interviews across Great Britain—projects that if an election were held tomorrow Reform UK would win 311 of the 650 seats at Westminster, 15 short of an overall majority but far ahead of Labour and the Conservatives. Because the Speaker and Sinn Féin abstentions lower the effective threshold for governing, YouGov’s central scenario would make Farage the only plausible nominee to command a plurality of MPs.

The numbers underlying that model are stark. YouGov’s projection puts Reform on 311 seats, Labour on 144, the Liberal Democrats on 78, the Conservatives on 45, the SNP on 37, the Greens on seven and Plaid Cymru on six (Northern Ireland is excluded). On vote share, the model has Reform at 27%, Labour 21%, Conservatives 17%, Lib Dems 15%, Greens 11%, SNP 3% and Plaid 1%. YouGov also reports wide uncertainty bands: Reform’s seat tally could be as high as 342 (a small outright majority) or as low as 271; Labour’s range runs from 118 to 185, while the Conservatives could fall to 28 or recover to 68.

Why Reform’s numbers look so large

Two structural forces help explain why a party on roughly a quarter of the vote could still emerge as the largest force in parliament.

First‑past‑the‑post rewards efficient geography in a splintered party system. Reform’s rise coincides with a dramatic fragmentation of the vote. The Electoral Reform Society (ERS) notes that the latest YouGov MRP implies the largest party would hold about 48% of Commons seats on just 27% of votes, an outcome it says reflects a system “being stretched beyond breaking point” as the two main parties’ combined vote slumps to 38%.

Margins are razor‑thin. Polling averages tell only part of the story; MRP is built to approximate seat outcomes. In YouGov’s latest release, small shifts could swing dozens of constituencies. As The Guardian summarised from YouGov’s write‑up, Reform is projected to be ahead by fewer than five percentage points in no fewer than 82 seats, enough that modest swings could cost Farage dozens of gains.

The ERS analysis underscores just how knife‑edge many contests could be. It estimates the average projected winning margin at 10 percentage points (versus 26 in 2019) and cites projected victories on exceptionally low shares: Labour taking Cardiff East on 22%, Reform taking Watford on 23%. In such conditions, small late swings, campaign effects or turnout differentials can transform the map.

Where the map moves; and why Labour is so exposed

YouGov’s seat‑by‑seat model is brutal for Labour not because its national vote is catastrophic, but because of where those votes are. Last year’s Labour landslide was built on “just enough” wins in thousands of close contests. That efficiency works in reverse when support ebbs across many marginals. YouGov’s model implies three‑quarters of Reform’s seats would be direct gains from Labour, and that more than half of Labour’s losses would go to Reform, particularly in England and Wales. Regionally, Reform looks strongest in the North East (21 of 27 seats) and in parts of Wales and the East Midlands; it remains weaker in London (six of 75) and Scotland (five of 57). The SNP, meanwhile, is projected to rebound to 37 seats, and the Lib Dems to 78, while the Conservatives suffer a historic collapse to 45.

The Guardian’s poll tracker captures the broader national mood music driving that geography: Reform averaging about 31% to Labour’s 21% at the end of September, a sudden and recent reversal as multiparty competition bites. It also records just how unusual Labour’s slump has been—its support falling 14.2 points in the first year after victory, the steepest drop for a new government in the PollBase series dating to 1983.

The next general election is not expected for just over two years; most in Westminster anticipate 2028 or 2029. Polls are snapshots, not predictions, and MRP models, powerful as they are, can only model the electorate that exists today. Volatility and multi‑party dynamics increase the modelling risk. YouGov itself emphasises the uncertainty in this environment.

So, how likely is a Farage premiership, really?

If Britain voted tomorrow on today’s figures, YouGov’s central projection would leave Farage best placed to form a government, either alone or as a minority administration. Sky News’s analysis goes as far as to say that once the Speaker and Sinn Féin abstentions are accounted for, it would be “all but impossible” for anyone else to assemble more pledged MP votes for prime minister. In theory a cross‑party coalition of Labour, Liberal Democrats, Greens, Plaid Cymru, the SNP and Northern Irish MPs could vote to block him, but Sky judges that highly unlikely, and even abstentions by opponents could leave Reform with enough support to carry the premiership vote.

But “tomorrow” is not the election. Two realities cut the other way. First, Reform’s advantage rests on dozens of tiny seat leads; a wobble of a few points would flip many of them. Second, when the choice is framed as a binary contest for the premiership, Labour has an advantage: a fresh YouGov survey for the Fabian Society finds voters prefer Keir Starmer to Nigel Farage as prime minister by 45% to 33% (22% don’t know), and prefer a Labour government to a Reform one by 46% to 34%, evidence that some of Reform’s current support may be “soft” in a real general‑election campaign.

What Labour (and others) could do to stop it

-

Make the contest binary, relentlessly. Labour’s clearest edge is in head‑to‑head preference. Converting a fragmented, multi‑party ballot into a felt prime‑ministerial choice, Starmer or Farage, could peel back anti‑Reform voters who might otherwise park a protest with the Greens or Lib Dems. The Fabian/YouGov numbers suggest this message has traction well beyond Labour’s 2024 coalition.

- Target the 82 knife‑edge seats. YouGov’s own figures indicate Reform is within five points in scores of constituencies. That points to a classic ground‑war strategy: seat‑level field operations, local messengers, GOTV and voter‑registration drives precisely where the margins are smallest. In a low‑plurality environment, turnout differentials can decide dozens of seats.

- Use tactical voting, and be honest about it. Under first‑past‑the‑post, small shifts can deliver wildly different results. The ERS’s examples of projected wins on 22–23% show how fractured contests can be. Informal local de‑confliction—Labour, Lib Dem and Green activists signalling where each is best placed—could prevent three‑ and four‑way splits that hand victories to Reform on minimal pluralities.

- Shore up the red wall’s soft spots and hold London. YouGov’s regional cuts point to Reform strength in the North East, Wales and the East Midlands, and relative weakness in London and Scotland. That argues for a resource shift: intensive economic and public‑service campaigning in deindustrialised seats where Labour’s vote has thinned, with an explicit urban defensive effort to block a London backslide that could offset losses elsewhere.

- Force a policy contrast where Reform is least tested. With multi‑party politics lowering the vote share needed to win seats, competence and implementation arguments matter more, not less. Labour’s task is to translate “who governs?” into “whose plans withstand scrutiny?”, particularly on the NHS, cost of living and public finances, areas where, in a general‑election frame, some voters who flirt with Reform may snap back. (This aligns with the head‑to‑head evidence that many voters still prefer a Labour government when forced to choose.)

- For the Conservatives and Lib Dems: choose a theory of the case. YouGov’s model has the Conservatives in fourth place by seats; the Lib Dems third. If the Tories continue to drift, Reform’s path gets easier; a Conservative recovery that re‑aggregates right‑of‑centre votes would likely squeeze Reform in dozens of marginals. Conversely, the Lib Dems’ ability to turn close seconds into wins in Tory‑held seats shapes the post‑election arithmetic, and the feasibility of any anti‑Reform voting‑down manoeuvres, improbable though those look today.

- Keep perspective, and discipline. The Guardian’s tracker shows Reform’s rise is recent and coincided with Labour’s unusually sharp first‑year slump. There is ample time for events, governing performance and opposition discipline to move the numbers before 2028–29. Over‑reacting to a single MRP output, as instructive as it is, would be a strategic mistake.

On the present trajectory, Farage has a plausible, even straightforward, route to No 10 if Britain voted today: become the largest party under first‑past‑the‑post, then rely on parliamentary arithmetic and the inability (or unwillingness) of everyone else to unite against him. But this is a path paved with small, fragile pluralities.

Many of Reform’s projected gains rest on wafer‑thin leads; a few points of movement, a better‑organised ground game by opponents or smarter tactical voting could keep Farage short of the critical mass of seats needed to convert polling into power. The election is years away; the race is fluid. For Labour and other parties, the task is not to panic—but to turn a noisy, fractured contest back into a choice.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!